Utah Jack’s diary follows The Sullivan’s days, weeks, and months at war in the Pacific during 1944-1945. More stories from his diary will follow.

The Pacific theater of operations mainly consisted of Island Hopping, a strategy developed by General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral William “Bull” Halsey in April 1942. The United States would use the islands in the Pacific Ocean by taking each, one by one from the Japanese. Using that island to launch air strikes on the next island, and hop from island to island, island group to the next island group, eventually reaching the Japanese home islands in 1945.

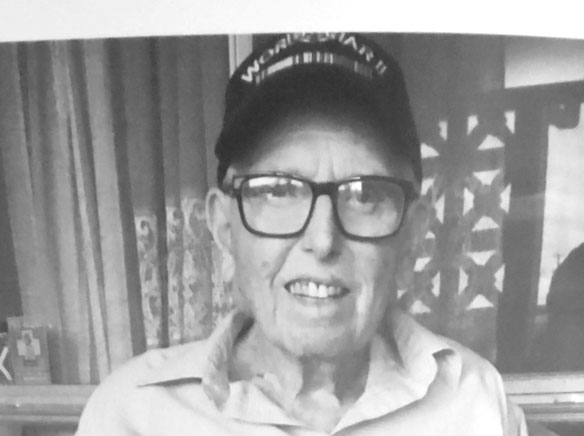

Jeffery R. Veesenmeyer’s new book, “Jack Clifton’s WWII Memoir,” which is based on the author’s special access to Jack’s secret diary and log. Mr. Veesenmeyer’s book, was very helpful in my conversation with “Utah Jack.” John (Jack) Clifton as told to and complied by Michael H. Pazeian.

I was born in Long Beach in 1926. My Dad worked at the shipyards in Long Beach. I was down there with him early and often in my life. I had the feeling the sea was calling me.

At age 17, June 1943, I quit high school and joined the Navy. During basic at Farragut Naval Training Station in Idaho, we trained on row boats and power boats. We marched a lot and trained with different weapons, mostly a carbine rifle. After basic training I was assigned to the USS The Sullivans.

On Nov. 13, 1942, the USS Juneau, a light-cruiser, was sunk by torpedo and bombing during the battle of Guadalcanal in the south Pacific. Aboard at the time were five brothers, all lost. USS The Sullivans, a Fletcher-class destroyer, was named for the five brothers. Mrs. Thomas F. Sullivan, the mother of the five Sullivan brothers christened the ship. Months later, after testing and trials, it was commissioned on September 30, 1943.

On April 4, 1943, the brother’s mom christened the ship at its launching in San Francisco. I was aboard the ship when it was commissioned. And during those five months the USS The Sullivans was completed, fully tested, and did its shakedown cruise. We did live-fire drills off San Diego with our 5-inch guns and our 20mm and 40 mm guns. The cruise, overseen by Naval Command, observed the ship and crew in every aspect normal for a ship of war.

By late December we left San Francisco and arrived at Pearl Harbor. I had started my diary. What I did was not legal. An officer caught me once copying from the ships log. “hey, you can’t copy that!”, he said. I said I was writing a letter to my girlfriend. “Let me see it.” I said it was about sex. He said, “OK”. And that was the end of his interest.

My duties aboard ship were as a carpenter’s mate. I was in charge of the two 26 feet wood motor whale boats and took the draft of ship (I measured how deep in the water we sat) every day. And I wrote that in the ships log each day. That is how I got what to write in my diary.

March 3, 1944:

We were in a storm. I was on the upper structure 50 feet away. I saw a sailor on the lower deck walking past the depth charge racks. He was hit by a wave and it appeared he broke his arm. Another sailor ran to help him. The next wave hit the ship, and both were washed overboard. The Sullivans kept going, then circled around to save the men. The sea was so rough it appeared they were drowning. I pulled off my clothes and dived in. I had always been a powerful swimmer, there was no hesitation in my mind that I could help in this situation. I learned later, the Executive Officer said no one can go into the water.

As he went to stop another sailor, who was going to dive in, I jumped over the side and swam out to the man who was 25 to 30 yards from the ship.

As I touched him on the shoulder I said, you’re going to be alright fellow. He had been fighting so hard to stay afloat he passed out. As we started back toward the ship, a second sailor swam up to us with a life ring and together we dragged him to the side of the ship.

They dropped a line to us and we put it around the unconscious man. As they started to pull him up the man’s arms went straight up and he almost fell back into the sea. I put my arms under his and they pulled both of us up. On deck everyone grabbed the one sailor, but not me and I fell back into the sea.

When I came back up to the top of the water I was 20 ft from the ship. I was so tired I felt I could not swim to catch up. I yelled, but no one was looking at me. I said to myself, I am not going to drown here and with a burst of energy I swam to the cargo net that had been put over the side during the rescue and I crawled onboard.

That night the Executive Officer came onn the PA system and called for all the men involved in the rescue to his office. I was on night lookout duty, where the PA could not be heard. I never heard the announcement. With the war on daily, the rescue was forgotten.

Five months later the men involved in the rescue heard the PA received the Presidential Citation from President Roosevelt. There was a ceremony aboard The Sullivans. I was sad that I was not one who was recognized.